As photography replaced drawing in some of its functions, the same is happening with synthetic media and photography. As we extend our plane of existence into becoming partly digital – think metaverse – tools like light-produced photography become inadequate. And while we accept a new representation of reality, the discourse should no longer be about whether it is true but instead on how we can use it to extend our ability to communicate.

The age of the pencil

At the end of the XIXth and for a big part of the early XXth century, newspapers would illustrate news stories with a drawing representing events described in articles. From simple portraits ( the Wall Street Journal was one of the last to give it up) to complete scene creation, illustrations would be the closest reality readers would experience.

Even when some publications started using photographs, those were often recreated, as photographers were not present when they actually happened. Robert Capa, the father of photojournalism, started his career by setting up images of events. It was perfectly acceptable, as readers, while well aware the photos were probably not taken at the actual moment the event happened, still recreated what it would have looked like. An illustration, a photo illustration.

Synthetic media is the next part of that evolution. Instead of recreating events with people and objects, computers generate them.

But is a representation of reality, even one that is so perfectly exact, still not true? Don’t we sometimes say that interpretation of reality feels more accurate than a photograph? Isn’t perception more important?

What is reality?

A couple of very insightful studies have been published regarding our relationship to synthetic media, deepfake, truth, and reality. One focused on “Deepfake detection by human crowds, machines, and machine-informed crowds.” In other words, how do we detect visual deception? The short answer is we don’t, or very badly. And machines are not better: In a recent worldwide competition, “the leading model achieved an accuracy score of 65% for automated deepfake detection”. Humans are a little better, but that is only because we also rely on context, something AI is not yet capable of doing. For example, when presented with a deepfake of Kim Jong-un, humans have the added ability to judge if what is being said would be something the leader of North Korea would say. AI would only look for tell-tell artifacts in the pixel or sound.

Interestingly, our emotions, particularly anger, appear to alter our ability to identify deepfakes. Not in making us judge a fake video as real but rather in thinking a real video is a fake. This explains a lot of what we are seeing on social media. The interpretation of fake news is very often led by anger.

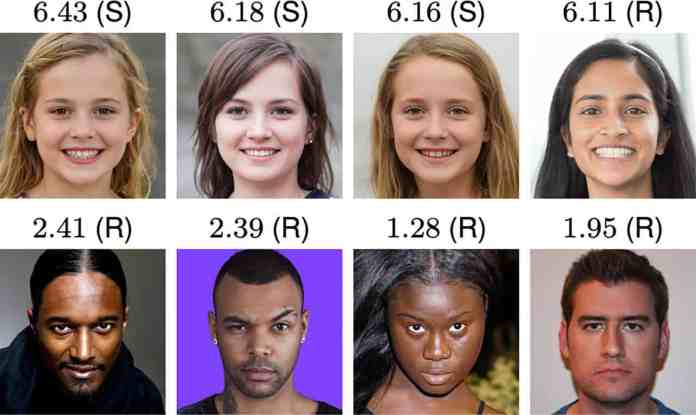

The second study, “AI-synthesized faces are indistinguishable from real faces and more trustworthy,” confirms the previous research finding. Humans are not good at distinguishing photos of real faces vs. ones created by a GAN. In fact, results hover around the 50% mark, making it very similar to a pure guess result.

On the question of whether ” synthetic faces activate the same judgments of trustworthiness,” the results are more surprising. With a 7.7% difference, synthetic faces were perceived as more trustworthy, regardless of whether they were smiling or not.

One of the conclusions states that this result might be “because synthesized faces tend to look more like average faces which themselves are deemed more trustworthy.”

What next?

Both these studies are good news for synthetic media companies like Bria, Vaisual, Synthesia. Since we are so helpless in detecting fakes and so willingly open to giving our confidence to computer-generated people, it shouldn’t matter how images are created. Whether it is via the transposition of light waves into pixels or via a game of computer-assisted trial and error, the result, it seems, is the same. We will continue to mostly believe what we see, helped by our confirmation biases and reinforced by social conformity.

It is good news because once the limits of credibility and trust are broken, there are no limits on what synthetic media can be helpful for. It is no longer limited to only representing that that cannot be photographed. Instead, as photography did with drawn illustrations before, it can become a more comprehensive reality description tool—the brush of the XXI, the photography of the metaverse. And as with previous artforms, find its masters.

It is good news because if it is a new language, it will extend the boundaries of our thoughts. No longer limited by the laws of physics, everything can and will be photo and video graphed. Past events, like the sack of Rome or currently invisible objects like quarks, will be “photographed.” Everything we can think about will be “photographed.” Or rather Synthographed. And those who build the tools to make it possible will be the winners of that evolution.

Main image Photo by Mike from Pexels

Author: Paul Melcher

Paul Melcher is a highly influential and visionary leader in visual tech, with 20+ years of experience in licensing, tech innovation, and entrepreneurship. He is the Managing Director of MelcherSystem and has held executive roles at Corbis, Stipple, and more. Melcher received a Digital Media Licensing Association Award and is a board member of Plus Coalition, Clippn, and Anthology, and has been named among the “100 most influential individuals in American photography”