What happens when images no longer need to be real, but still demand authority?

When the BBC, the State Department, or Apple publishes an AI-generated image, viewers trust it. The label saying “AI-generated” doesn’t change that. If anything, the label reinforces trust – it shows the institution isn’t hiding anything.

But here’s the problem: the label discloses how the image was made. It doesn’t limit what the image can do. A photorealistic synthetic image still looks like evidence and can still feel like documentation. The viewer’s brain processes it as truth, even when the fine print says otherwise.

While labels describe intent, visual form drives perception. And perception wins.

The disclosure becomes theater, as institutions get credit for transparency while still wielding the full persuasive power of photorealistic imagery.

Plumbing vs. Architecture

C2PA and similar provenance systems answer essential questions: What is this image? Where did it come from? Who made it? This is infrastructural work, ensuring the pipes don’t leak, verifying the chain of custody, and creating an auditable record of the image’s history.

But infrastructure does not decide what flows through the pipes. Provenance tells us an image is synthetic. It does not tell us whether deploying that synthetic image constitutes an abuse of power, a breach of professional mandate, or a violation of public trust.

That determination requires governance. Ethics is the constitutional architecture that determines which institutions may use synthetic imagery, how they may use it, and whether they must disclose it. And right now, we have plumbing without architecture.

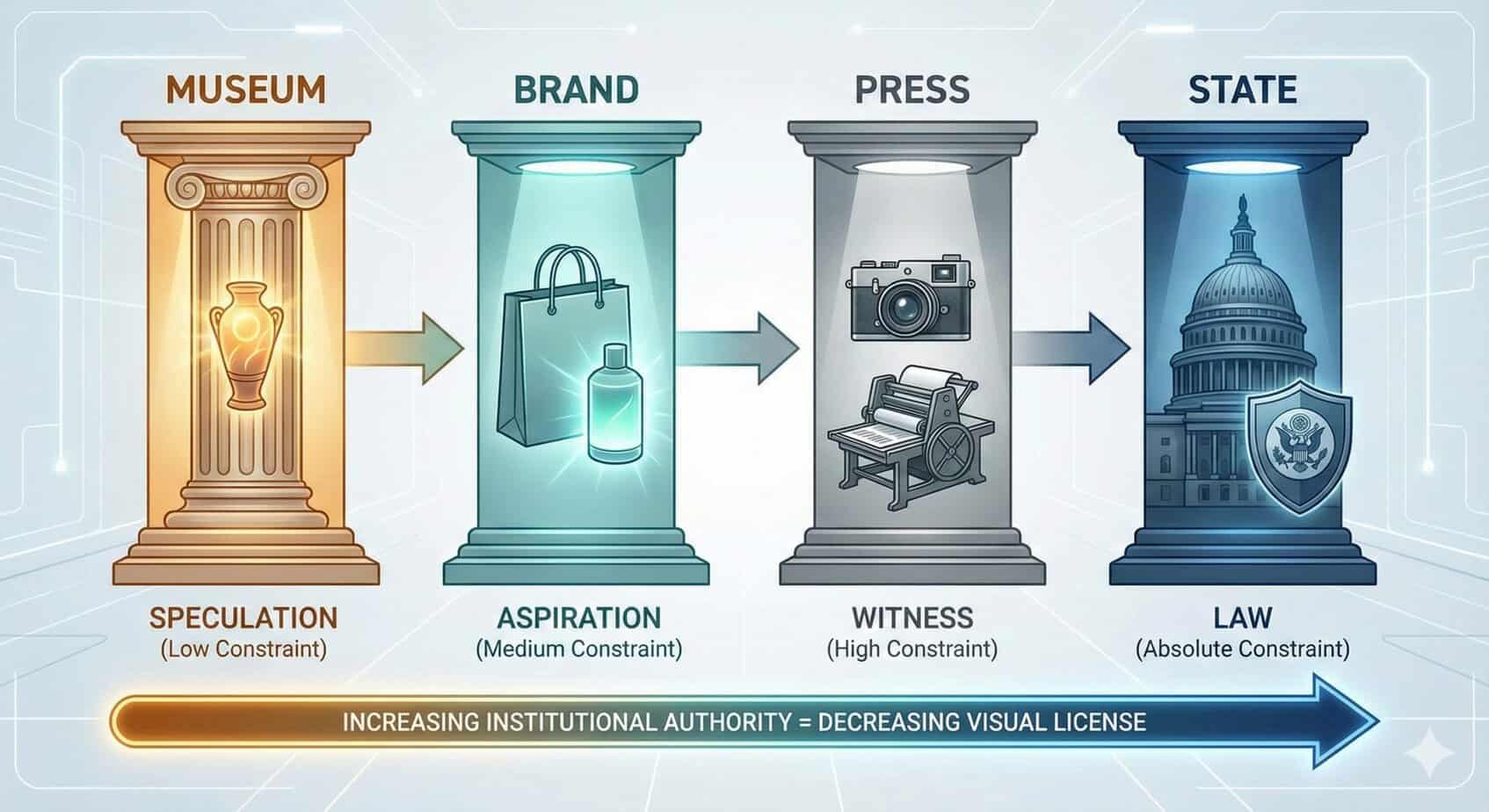

The Hierarchy of Constraint

We need a sliding scale of visual permissibility. The more authority an institution wields, the less blind freedom it should have to deploy synthetic imagery. Constraints should be based on institutional role in the social contract, not on technological capability.

I. The Museum: The Space of Speculation

Role: Education, exploration, “What might have been.”

Museums operate under a high license. A museum can use AI to reconstruct a ruined temple, visualize a black hole, or imagine what a medieval marketplace looked like. The audience enters a museum expecting interpretation. The social contract allows for useful fiction because the institutional mandate is pedagogical, not evidentiary.

When the British Museum creates a digital reconstruction of the Parthenon as it appeared in 432 BCE, no one is deceived. The context, a museum, already signals speculation. The constraint here is minimal because the stakes are educational, and the audience understands they are seeing scholarly imagination rendered visible.

II. The Brand: The Space of Aspiration

Role: Commerce, desire, “What you could have.”

Commercial imagery operates under a conditional license. An IKEA catalog can be entirely 3D-rendered. A fashion brand can generate synthetic model shots and lifestyle contexts. A sneaker ad can be AI-generated from top to bottom.

The constraint comes from what we might call the “Digital Twin” rule: the image can be synthetic, but the product attributes must be true. If the AI adds a feature the product lacks, or depicts the sofa as larger, the fabric as softer, or the shoe as more durable than reality, it crosses from marketing into fraud.

This works because aspiration is the explicit contract. No one believes the model actually lives in that fancy apartment. The reckoning moment, product arrival, checks the material claim while leaving the aspirational claim intact. The brand has a license to manufacture desire, but not to manufacture false specifications.

III. The Press: The Space of Witness

Role: Record, accountability, “What happened.”

Journalism operates under severe constraints. The press exists to create an independent record of events. When a news outlet uses AI to “reconstruct” a war zone scene because it couldn’t get a photographer there, it trades on borrowed credibility. They use the aesthetic of truth, aka photorealism, without the substance of truth, which is presence.

The problem isn’t illustration; the problem is photorealistic simulation: A “reconstruction” labeled as “illustration” still represents a failure of journalistic mandate. It turns news into a parable. The image says, “This is what it looked like.” Still, journalism’s obligation is to show what it actually looked like, or to admit the absence of documentation rather than fill the void with synthetic simulation.

As photojournalism becomes economically unsustainable for photojournalists, outlets will face increasing pressure to use AI reconstruction to maintain visual completeness. But visual completeness is not the same as truth. The gap where the photograph should be is itself information. It tells us something was inaccessible, dangerous, or deliberately hidden. Synthetic reconstruction erases that gap and replaces it with algorithmic confidence.

Photojournalism is the representation of the world as it is; synthetic photorealism is an illustration of the world as it could be.

The press should be permitted synthetic imagery only in clear and explicitly hypothetical contexts: “Here is what this policy might look like in practice.” “This is a visualization of how the attack may have unfolded based on witness testimony.” The genre must be signaled not just through labels, but through formal differences that prevent the image from functioning as documentary evidence.

IV. The State: The Space of Law

Role: Authority, evidence, “What is fact?”

Government agencies function as ultimate arbiters of official reality. State imagery acts as what we might call “soft evidence”-not admissible in court but functionally evidentiary in public consciousness. When a transit authority uses AI to show “safe subways,” or the Pentagon uses AI to “visualize” a conflict zone, or a public health agency generates synthetic imagery of disease transmission, they are effectively legislating reality.

Even with disclosure labels, the official seal overwhelms the asterisk. The state does not merely report on reality; it defines what counts as real in policy, law, and collective memory.

The constraint here must be near-absolute. Government agencies should reserve synthetic imagery for explicitly hypothetical scenarios: disaster preparedness simulations, threat modeling, and policy visualizations of proposed infrastructure. Never for claims about current conditions. When the state deploys photorealistic synthetic imagery about border activity, public safety threats, or economic conditions, it creates an optimized official record that makes the messy, inconvenient reality of actual photography look inferior by comparison. It doesn’t just alter reality; it influences opinion.

Federal oversight bodies have begun warning about these scenarios, though mitigation recommendations remain focused on transparency measures rather than usage restrictions.

The Right to Reality

The core problem is simple: institutional authority- public trust- supersedes metadata. When powerful entities deploy synthetic imagery, the label doesn’t constrain the image’s persuasive force. The viewer processes the image through the lens of who published it, not how it was made.

This makes synthetic imagery a tool that amplifies existing power. And like any tool capable of amplifying power asymmetrically, like surveillance systems, or weapons, or propaganda channels, it requires clearly defined rules about legitimate use.

The question is not whether synthetic imagery should exist. AI images are perfectly legitimate tools. The question is whether institutions that hold public trust should be permitted to leverage the persuasive force of synthetic imagery while claiming the mantle of objective documentation.

Like any tool capable of harm, they require context-specific rules that match use to mandate. A museum may speculate. A brand may aspire. The press must witness. The state must document.

Provenance is necessary infrastructure. But infrastructure serves governance, not the other way around. We built the tools to authenticate synthetic images. Now we need to define the boundaries on how institutions deploy them.

Author: Paul Melcher

Paul Melcher is a highly influential and visionary leader in visual tech, with 20+ years of experience in licensing, tech innovation, and entrepreneurship. He is the Managing Director of MelcherSystem and has held executive roles at Corbis, Gamma Press, Stipple, and more. Melcher received a Digital Media Licensing Association Award and has been named among the “100 most influential individuals in American photography”